- Home

- Robert Gluck

Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe Read online

ROBERT GLÜCK (b. 1947) is the author of two novels, Margery Kempe and Jack the Modernist; two short-story collections, Elements and Denny Smith; and Communal Nude: Collected Essays. His books of poetry include Reader, La Fontaine with Bruce Boone, and In Commemoration of the Visit with Kathleen Fraser. He made an artist book, Parables, with Jose Angel Toirac and Meira Marrero Díaz, and he wrote the preface to Between Life and Death, a book of paintings by Frank Moore. With Camille Roy, Mary Burger, and Gail Scott, he edited the anthology Biting the Error: Writers Explore Narrative. In the late 1970s, Glück and Bruce Boone founded New Narrative, a literary movement that makes use of self-reflexive storytelling and essay, lyric, and autobiography in one work. Glück served as the director of the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University, where he is an emeritus professor. He was the co-director of Small Press Traffic Literary Center and an associate editor at Lapis Press. He lives “high on a hill” in San Francisco.

COLM TÓIBÍN is the author of nine novels, including The Master and Brooklyn, and two collections of stories. His play The Testament of Mary was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Play in 2013. He is the Mellon Professor of the Humanities at Columbia University.

MARGERY KEMPE

ROBERT GLÜCK

Introduction by

COLM TÓIBÍN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 1994 by Robert Glück

Introduction copyright © 2020 by Colm Tóibín

All rights reserved.

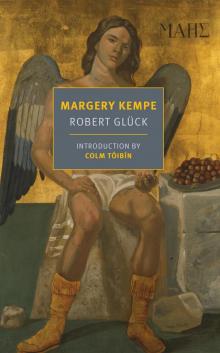

Cover image: Yannis Tsarouchis, Twelve Months, May, 1972; courtesy of the Yannis Tsarouchis Foundation

Cover design: Katy Homans

“My Margery, Margery’s Bob” originally appeared in Shark, no. 3, fall 2000, and was collected in Communal Nude: Collected Essays by Robert Glück, published in 2016 by Semiotext(e).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Glück, Robert, 1947– author. | Tóibín, Colm, 1955– writer of introduction.

Title: Margery Kempe / by Robert Gluck, introduction by Colm Toibin.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2020] | Series: New York review books classics | Copyright © 1994 by Robert Gluck, introduction copyright © 2020 by Colm Toibin.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019039532 (print) | LCCN 2019039533 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681374314 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681374321 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Kempe, Margery, approximately 1373– —Fiction. | Women mystics—Fiction. | Gay men—Fiction. | GSAFD: Love stories. Classification:

LCC PS3557.L82 M37 2020 (print) | LCC PS3557.L82 (ebook) | DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019039532

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019039533

ISBN 978-1-68137-432-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

Introduction

MARGERY KEMPE

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

My Margery, Margery’s Bob

INTRODUCTION

Some way into Margery Kempe, Robert Glück ends a chapter with a question: “How can the two halves of this novel ever be closed or complete? Or the book is a triptych: I follow L. on the left, Margery follows Jesus on the right, and in the center my fear hollows out ‘an empty space that I can’t fill.’” It is characteristic of this free-wheeling, intriguing, and self-aware novel to shift tone and change direction so abruptly. The two halves of the novel referred to are, on the one hand, the story of the narrator’s love affair with a handsome, evasive, and elusive American aristocrat, the so-called L., and, on the other hand, the story of Margery Kempe, an English Christian mystic, born around 1473, who wrote what is often called the first autobiography in English.

The centerpiece of the triptych, rather than an empty space, is actually a daring literary style that favors startling images that move from late fourteen- and early fifteenth-century England to late twentieth-century America with suddenness and ingenuity. The sentences have a way of holding their nerve, like someone driving on ice braking hard on a sharp turn. The book plays not only with time but with tone. It allows moments or emotions from one story to leak into the other, in the same way as one thought in consciousness loses its sway and lets something more immediate take its place, only to be supplanted in turn by another thought or image. What connects the stories and weaves its way through the book is the theme of death, death that comes from hopeless infatuation, from sexual desire, from plagues new and old.

Nothing is schematic in Margery Kempe. Its procedures, connecting the deeply personal with the experimental, are underpinned by a theory of fiction-writing called New Narrative that was proposed by Robert Glück and some associates in San Francisco in the 1970s.

The competing narratives in Margery Kempe work against expectations; they obey no rules. The novel allows the stories and voices to wander, as the mind might wander, following arrangements that are more organic than orderly. The book does not accept the idea of story itself as a single line and does not have sections that are intact, contained, discrete. It seeks to undermine the very notion of the master narrative, or even competing narratives, to be replaced by a sort of porousness or flow.

“My palette is a sentence. Each next sentence can start at a very different place and so that makes for a kind of porousness, which is a quality I want,” Glück said in an interview with EOAGH, in the spring of 2009. There are sentences in the book that seem to establish verisimilitude, but then the sentences coming next appear to parody that very possibility. There are moments that set up a time and a place to be followed by language that is deliberately out-of-date.

In the same interview, Glück said: “In Margery, for instance, all the birds are real, even in her visions of the Holy Land, the right birds appear where and when they should. All the clothing is accurate. Other things are purposely anachronistic.”

While the novel thus undermines stable ideas of time, it is held together by a delight in what phrases and sentences do, by a rhythmic vivacity in the texture of the prose that compels the attention, enters the nervous system almost stealthily until the structures that the book sets out to question, having been purified by holy fire, return to us, ready to be taken seriously.

The novel is filled with images of the body, of pure carnality and quick desire. In their introduction to the anthology Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977–1997, Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy wrote: “Before there was crowd-sourcing, Bob [Glück] was asking his friends and students to provide lists of body sensations that he subsequently sifted into his novel on Margery Kempe.” The novel allows religious devotion itself to soar above the mere business of prayer and obedience into a realm that is filled with the possibilities of bliss and fulfillment, not only for the soul but for the body, the body that holds the center of each side panel of the triptych.

The figure of Jesus in the novel is brought to earth. He is all sex and sinew. Margery’s devotion is not to the word Jesus preached or the promise of heaven, it is to his flesh, the living reality of his presence on earth, his mundane existence. His lubricity, rather than his preaching, is his allure.

“The tension between masculine-feminine and inside-outside pervades all levels of my community,” the narrator writes. On the same page, it is as though the narrator’s desire for L. and Margery’s for Jesus become interwoven, just as, soon afterwar

d, words like “man,” “woman,” “me,” “I,” “he” start to become interpenetrative. Soon the sexual desire in the novel becomes a single one, or one in which all boundaries have been threatened. “I push myself under the surface of Margery’s story, holding my breath for a happy ending to my own.”

If this is intense, then its earnestness will not be allowed to dominate. It will soon be thwarted by Jesus saying to Margery that he would like to send her “to Jerusalem and to Rome” and Margery replying: “Jesus, where will I get the money?” For any reader, “Jesus” here will have two meanings: one to denote the figure in the New Testament, the other a casual word often placed at the beginning of a sentence to express wonder, worry, or surprise. No matter what, the tone has shifted. If the reader’s expectations are simple, they will have been wrong-footed. The narrative will have claimed a small victory over easy expectation and gained energy accordingly.

In Part Two of the book, Margery, complete with her visions and free of all fear, sets out with a group on a pilgrimage. She speaks her mind and that alarms her fellow pilgrims. The writing about nature and travel comes to us ambiguously, many declarative sentences denoting the look or feel of things as in an ordinary novel, but each of them having an edge of pastiche, put there for show, as though cut and pasted from an imagined kitty of earlier sources to make sure we take nothing for granted.

Here we have an early fifteenth century swirling with images of sex and gender, and then this pastoral landscape disrupted by contemporary concerns, as in: “Women carded and combed, clouted and washed, and peeled rushes. . . . One woman became a man when he jumped over an irrigation ditch and his cunt dropped inside out: gender is the extent we go to in order to be loved. His mittens were made of rags.”

That last sentence may seem unnecessary, or just tagged on, but it is not. First of all, after the previous assertion, which requires us to stop for a moment, the sentence about the mittens seems natural, encouraging us to read on. It is the sort of odd detail that fiction thrives on, appearing to be part of the random visible world rather than the writer’s efforts to manage reality and create schemes. Also, the sentence has a rhythm and a sound that could be from a ballad.

When stray sentences in the novel, such as “They talked till stars appeared above the elms,” have a full iambic pentameter sound, it is as though they have earned their keep against the surrounding mixture of the dead serious, the parodic, the flippant, the urgent, and the real. As in “His mittens were made of rags,” they have a way of restoring the possibility of innocence to a simple statement in sonorous prose. In Communal Nude: Collected Essays, Glück wrote: “In my novel Margery Kempe . . . each sentence is a kind of promise, an increment of hope that replaces the broken promise of the last sentence. What is that promise? That the world will continue, that one image will replace the next forever—that is, the world will respond to your love by loving you back. The silence is that of a world about to be born.”

Just as Margery goes to Venice, so too do our twentieth-century lovers. When Glück writes “Venice grew crowded as spring progressed. At dusk the population spilled into the streets and piazzas, sweetly murmurous, still dazed from the light,” it is playfully clear that this is what both Margery and the lovers experienced. They have been captured in time. In Communal Nude, Glück wrote: “History is endlessly porous; so instead of creating a middle distance, I used extreme close-ups, historical long shots, and autobiography.”

They have also been captured in prose, brought into our presence courtesy of style. There are times when the couplings between the narrator and L. require a style that is lofty, distant, made up of disparate moments, creating images of lovers who are singularly unclose. Margery and Jesus, on the other hand, experience a coupling that is more passionate and open and demands the unembarrassed style of romance writing: “She lay facing him, her red hair fanned out behind. Arms and legs draped over each other, lips touched in ardent peace.”

There are moments in the book that are designed to give us a spectacular shock. These mostly center on the figure of Jesus. Glück is unafraid of offering him a full humanity and a frailer divinity. It is noted early in the book that “He had been crying all weekend.” Later, he states, “I spasmed eleven times.” Later again, “Jesus and Mary squatted, making little cries, then looked curiously at each other’s shit.” This is no more blasphemous than Renaissance paintings showing Jesus’s bare legs and thighs, his naked torso, his face in ecstasy and agony. He has always been there for us, flesh and blood.

Such waverings in the book from the sacred to the profane mirror Glück’s own movements as an author. He seeks both to control the tone and follow the aleatory flow of his own inspiration. He wishes to tell both Margery’s story in all its fervid strangeness and his own in all its calm melancholy. He wishes to invoke the shock and pain of the Crucifixion in a time when gay men were dying of AIDS. But he also wishes to intercede on behalf of the narrator as intruder, interloper, the man who wrote the book and will have to live outside its pages into the future: “I am drawn to modernism but my faith is impure. I am no more the solitary author of this book than I alone invent the fiction of my life. As I write, I read my experience as well as Margery’s. Is that appropriation?—that I am also the reader, oscillating in a nowhere between what I invent and what changes me?”

Margery comes back to England. Dates are given, as elsewhere in the book, to establish verisimilitude. For Glück, this is a loaded idea, one he seeks both to explore and explode. It matters that the reader believes that the difficult truth and moments of pain he experiences with L., his lover, are true, or as true as he can make them, and as revealing as Margery was in her writing when she sought to reveal the quality of her devotion and vision.

Our narrator has visions too: “I raise my eyes to a dark window seven stories high where L. lives in New York. The window is lit, he is flesh and blood, he leans into another man in amusement and then warmth. I whisper his name to elevate this story with the strength of my sexuality.”

In chapter 41, it is as though two mystical unions have become one, as Jesus almost becomes L., as the prose moves into italics and stray phrases. In Communal Nude, Glück wrote: “I draw together the emergence of the modern self and the end of the modern self, the decaying society in which Kempe lived, the decaying society in which I live, and our respective plagues. L.’s ruling-class status equals the divinity of Jesus. . . . The two stories are like transparencies; each can be read only in terms of the other.”

Three chapters later, we read: “It was 1420; experience was crumbling.” In Glück’s world, the crumbling of experience is part of the deal, including the experience of reading. In the interview in EOAGH, he said: “The best reading is an uncertain reading. . . . We are educated to think that we should be able to know the meaning of a piece of writing, but what if the intention of the writing is to throw us into confusion, induce a state of wonder, and unravel the basic tenets of our experience?”

The rest then, for everyone involved, is a plot that cannot be given away. It is all the more precious because it has been foretold, and its telling includes cries and whispers as well as questions: “How do you find your way in empty desert when you have become that desert?”

—COLM TÓIBÍN

MARGERY KEMPE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For the most part I used B. A. Windeatt’s translation, The Book of Margery Kempe, phrases of which remain undigested in my book. I relied on Louise Collis’s Memoirs of a Medieval Woman, along with other sources, such as Three Prose Works by John Aubrey, the notebooks of the eighteenth-century naturalist Gilbert White, and miniatures from books of hours. I found the epigraph for Margery in Michael Baxandall’s Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy.

As I say in chapter thirty, I gathered observations and anecdotes about the body and dropped them into my shadowy fifteenth-century characters. I wanted to mingle the near and distant, present a jumpy, heterogeneous physical life, and asse

rt the present, which projects in every direction. I owe a debt of gratitude to the following friends who gave me their observations in the form of notes: Steve Abbott, Honor Johnson, Sarah Schulman, Thom Gunn, Fanny Howe, Lyn Hejinian, Robin Trembley McGraw, Susan King, Bonnie Kernes, Rachel Barkley, Jane Longaway, Matias Viegener, Gina Hyams, Lisa Bernstein, Bo Huston, Frances Jaffer, Carla Harryman, Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Warren Sonbert, Elin Elisofon, Camille Roy, Bruce Boone, Michael Amnasan, and Frances Phillips.

My thanks to Ed Auerlich-Sugai and Tom Thompson for their help with angels.

I am grateful to my friends who critiqued one or more of the numberless drafts of this book: Kathleen Fraser, Bruce Boone, Carolyn Dinshaw, Edith Jenkins, Richard Schwarzenberger, Thom Gunn, Camille Roy, Carla Harryman, Bo Huston, Phyllis Taper, John Garrison, Kevin Killian, Aaron Shurin, Lydia Davis, Clara Sneed, Chris Komater, and Earl Jackson, Jr.

Thanks to Mirage Period(ical) and Five Fingers Review for publishing excerpts from this work.

Finally, my thanks to the Djerassi Foundation and to the MacDowell Colony for their support.

for Camille Roy, Angela Romagnoli, and Reese Romagnoli

And then too you must shape in your mind some people, people well-known to you, to represent for you the people in the Passion. . . . When you have done this, putting all your imagination into it, then go into your chamber. Alone and solitary, excluding every external thought from your mind . . . moving slowly from episode to episode, meditate on each one, dwelling on each single stage and step of the story.

—The Garden of Prayer

written for young girls in 1454

PART ONE

Margery Kempe

Margery Kempe